All maps are distortions

of reality, said Mr. Montello, who studies how people perceive space and

geography. The earth is round and land masses are difficult to accurately

draw on a two-dimensional plane. But different maps serve different purposes.

For Mr. Montello, who has

a doctorate in psychology and serves as the chairman of the university's

Cognitive Science Program, the meaning a map conveys is important.

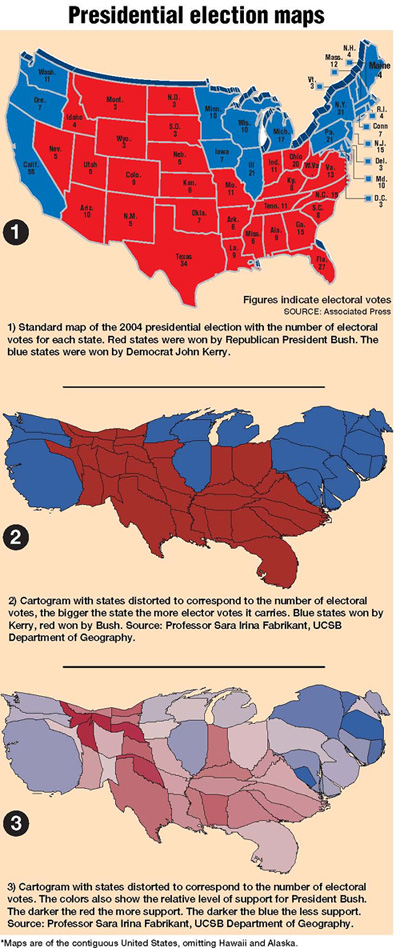

The red of giant western

states like Wyoming, with its population of less than 500,000, dominates

the electoral map used by most newspapers.

But try and find the blue

dot of the District of Columbia, which has close to 600,000 people. There

are more people in a few blocks of New York City than the whole state

of North Dakota, but you would probably have an easier time finding Bismarck

than the Bronx in most of the national maps used to chart the election.

There are some notable exceptions

to that rule. Both the New York Times and the Los Angeles Times this week

have included different maps to chart such things as the depth of support

for each candidate in each county across the nation. And both papers have

included maps that distort the shape of states, enlarging and shrinking

them based on their electoral votes.

It is ironic that distorted

maps can actually convey more meaning than the standard representations

of the United States, said Sara Fabrikant, a geography professor at UCSB.

Ms. Fabrikant created her

first election map the day after the 2000 presidential election. The Swiss

native wanted to understand the close race. She was perplexed by the message

that the election was too close to call, yet the election maps used on

television and in the newspapers showed a nation colored mostly Republican

red.

"I'm not an American citizen

and I didn't understand the electoral vote system until I put it on a

map," she said.

The traditional political

map made it appear that President Bush was winning hands down.

"In essence they are using

the wrong visual form," Ms. Fabrikant said.

Using cartograms, maps that

include statistical data to add color shading or distortions in shape,

she created a map based on electoral votes that showed a more even split

in votes between candidate Al Gore and Mr. Bush in the 2000 race.

She did it again this year,

posting her maps online the day after the race.

The distorted maps range

in color from a light blue to light pink, showing both the intensity of

support for each candidate and the relative number of votes each got.

(One of her colleagues said the distorted national map looks slightly

like an upsidedown donkey, but Ms. Fabrikant said it was pure coincidence

and that she has no party affiliation.)

"What you can really see

is the urban and rural contrast in voting," Ms. Fabrikant said.

The cartogram contracts the

empty land and expands the populated cities.

Over the summer she delivered

a paper on the 2000 race, "Blue & Red America," to a group of German academics.

She's also added other variables to her maps and included a breakdown

by county. What's striking is that displaying the data in different ways

begs new questions. On one map she included major rivers and highways

and found a line of blue snaking up the Mississippi. In another she saw

an arching band of blue extending through several southern states.

The apparent patterns prompted

her to wonder if the lines followed the same migration routes of blacks

who moved north for jobs, or whether they simply follow urban development

along the river front. Ms. Fabrikant said she would like to work more

with a political scientist to investigate those patterns.

Making these maps isn't about

politics, she said, but communicating information.

"Basically what has been

driving cartography for 5,000 years is the acknowledgement that a picture

really is worth a thousand words."

FYI

Sara Fabrikant's election

maps and information about cartograms can be found at her Web site:

www.geog.ucsb.edu/~sara/

|